March 13, 2024

Member Spotlight: NextGen Jane

NextGen Jane is pairing innovative diagnostic technology with insights from tampons to help women answer questions about their reproductive health

NextGen Jane is on a mission to empower women with a better understanding of their reproductive health—and it all starts from a small piece of spun cotton. The average woman will use more than 9,000 tampons in her lifetime, which NextGen Jane has learned carry several indicators about women’s reproductive health.

The innovative Oakland-based diagnostics company is using multi-omic approaches to delve into what data can be derived from analyzing menstrual blood. They hope that information gleaned from it could help women better understand their reproductive health, as well as issues such as endometriosis and infertility. Ten percent of women are affected by endometriosis, a painful condition that typically requires surgery to diagnose and can lead to infertility; and up to 77 percent of women will develop fibroids.

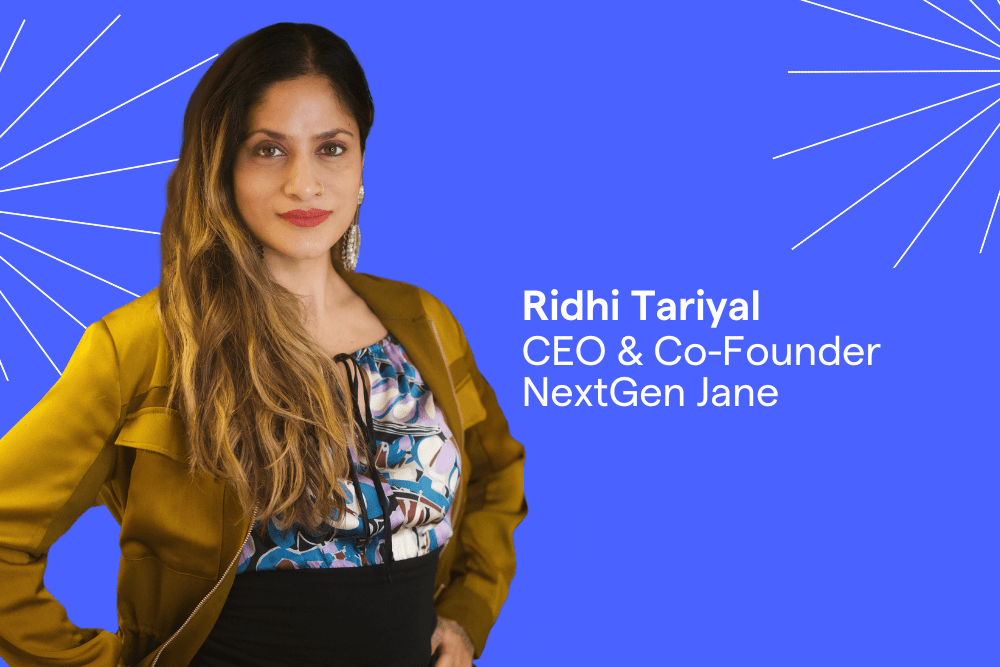

Led by CEO and Co-Founder Ridhi Tariyal, NextGen Jane is looking for a better and less invasive way to address women’s health concerns. Since its formation in 2014, much of the company’s origin story traces back to the frustrations Ridhi experienced in navigating our healthcare system. NextGen Jane is currently working on clinical studies for endometriosis and infertility in its menstrualome project—the term the company coined for the collection of data and information on menstruation—and is recruiting women to submit samples through provided collection kits that include a set of organic cotton tampons. In its early days, NextGen Jane was accepted into Illumina’s accelerator’s program. More recently, it was awarded a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Development, part of National Institutes of Health, in 2022.

In this month’s Member Spotlight celebrating Women’s History Month, we spoke with Ridhi about the evolution of the company, how to build a diagnostics company around an issue that lacks historical data and studies, finding supportive allies, and ways that women can best advocate for their health.

What is the latest news on the menstrualome project? How many samples have you collected?

We’re beyond 2,000 tampons at this point, which have been collected from around 350 individuals. The beauty of a tampon over a biopsy, is that you can easily collect multiple tampons from each person, which is critical to building up an understanding of the menstrualome and how it changes over time.

It took a while to map out what the ‘menstrualome’ even means. We collect tampons at many days across a single cycle, and many cycles across many years. We’ve had individuals who have been in our studies for years, and people who have transitioned from our baseline study to our pregnancy study. It’s been a nice demonstration of the ability to collect samples serially and longitudinally—you don’t have to go to the doctor’s office. It’s minimal effort. All that’s required is using a tampon for a limited amount of time while you are on your period, and we send you a kit and you mail that back in. Because that process is so simple we have the ability to follow patients over time. We’ve received tampons from all over the United States, and as far away as Hawaii. It’s allowed us to answer really important questions about the menstrualome: if you looked at a tampon from someone at the start of the period (day one of the cycle) compared to a tampon from the same individual toward the end of their period (day 5), how similar or dissimilar are those sample types? It’s a profound question that is not necessarily answered in [existing] literature but is necessary to establish.

Our focus has been maximizing the number of tampons collected from a cohort of individuals, so that we can begin to understand what’s happening with these individuals within one cycle and within multiple cycles within a year, two years, and so forth.

What data are you finding that is different between a day 1 tampon and a day 5 tampon? Is there anything about the data that surprised you?

It’s been a long, ten-year journey and we’ve had a lot of interesting findings. We collect both vaginal and menstrual samples with the tampon and sequence both human and microbial environments. In the early days we were doing 16S sequencing but we’ve moved on to metatranscriptomics, which can provide much more granular information on the activity of bacteria.

When we were doing 16s sequencing, we were looking at relative abundance of certain bacteria. We were collecting samples from healthy volunteers who had no reproductive pathology–both before and during their cycles. Before their cycle, some patient’s vaginal microbiome was mostly lactobacillus and looked completely normal, but their menstrual sample showed complete dysbiosis indicative of infection. A high abundance of things like gardnerella, a pathogenic bacteria, were found in these sample, yet they would have no symptoms. If a patient has gardnerella bacteria in high abundance, that’s an indication of something.

Having access to menstrual information and molecular information is uniquely insightful. Two questions we use as a through line in our thinking as a company are: How finely can I characterize this data? And what is menstrual effluence showing me that no other sample type can?

How do you recruit men to collaborate on a project that researches something that they don’t experience? How does that translate to getting funding, considering VC firms are often male-dominated?

The solution is to find the men that understand the problem already and have a deep interest in it. That’s a much easier mountain to climb than convincing someone who isn’t interested in the problem fundamentally. You always find that there are scientists—biologists and data scientists—that lean in because the science is so complex that it’s interesting. If you are a good scientist, that’s what excites you.

It’s the same with investors. I realized very quickly that my efforts were better spent in finding investors who had a natural interest in how big of a market opportunity this is. Women are a huge constituency—they have money, are vocal, and are becoming better advocates for themselves and navigating the healthcare system. If you’re building products that you want to see an ROI on, instead of beating your head against a wall trying to convince someone who doesn’t see the market opportunity, just find investors who say, ‘Of course, that’s a big market! Let’s figure out together how to get there.’ That’s the problem I seek to solve, whether it’s in science collaborators, investors, or even people who are working on policy, is finding anybody who’s willing to lean in.

Two questions we use as a through line in our thinking as a company are: How finely can I characterize this data? And what is menstrual effluence showing me that no other sample type can?

What is your biggest challenge right now?

There are three main challenges, two are macro and one is micro. One big challenge when we got started in this field is there were so many questions that were unanswered. Oftentimes you rely on the literature and the foundation that’s been built in academia. There was not a lot there, in terms of a clear understanding of what the menstrualome was like. The question of ‘how is a day one tampon different from a day five tampon?’—there was no paper I could pick up that had that information.

Women’s health is historically understudied, there’s a lot of foundational science that doesn’t exist. We know that so many of the animal models are male animal models, and women were not well represented in many clinical trials. Very recently, there was concern because COVID-19 vaccines seemed to have an impact on menstrual cycles that was completely missed in the clinical trials. I don’t think the motivations for that are nefarious—the hormone cycle is complex.

Another challenge is that diagnostics in general is an extremely tricky and challenging space to be in. We think that diagnostics are the linchpin of healthcare—they are what gives you information faster and sooner, and that makes all the difference in disease progress. Healthcare innovation is deeply tied to the ability to detect and track disease. Yet diagnostics are not reimbursed like drugs are reimbursed. Even if you develop a test that works well, you have to prove to insurance companies and payers that you can actually save them money over a 12- to 18-month timeline for their covered population.

Lastly, there’s always a challenge in recruiting faster [for our clinical studies]. Whether it’s a therapeutic or diagnostic company, the faster you enroll, the faster you get to market. A key target demographic that we need is people struggling with infertility who know it’s not because of endometriosis.

How can women better advocate for their reproductive and menstrual health concerns?

Women often normalize their own pain. We’ve talked to endometriosis patients for years now, and they will tell us things like: ‘the first time I got my period, I bled through my mattress.’ When we asked if they knew they were experiencing something that was non-normal, there’s two types of answers we get: ‘no,’ or ‘who would I have asked?’ Oftentimes, their family or peers shame them or give them the indication it’s not talked about or that it’s normal.

When seeing a clinician, come in with data. If you are experiencing something that you’re not sure is real [such as painful periods or excessive bleeding], you’re most likely going online looking for answers. Everyone does that, and it’s okay. But track it and say, ‘for the next three months, I’m going to try to be quantitative about this.’ How painful is it on a scale of one to 10? You can find pain scales online that have been calibrated in literature. For instance, take note if your pain was a 9 on day 1, you had to change your tampon every 30 minutes, or you take time off of work or school because of it.

All of these things are real quantitative features that clinicians will use. If you came in with this cataloged history to say, ‘I’ve been paying attention’ and having it longitudinally tracked, I think it would be hard for them to ignore. And do your research to understand your treatment options.

What advice do you have for young women entrepreneurs in the biotech industry?

You have to be capital efficient. I think that oftentimes women entrepreneurs are given smaller check sizes. And so I always say, ‘they expect you to do more with less.’ And if that’s the case, try not to build up overhead and infrastructure that you may not need. We have tried to, at NexGen Jane, be very capital efficient and put as much money into data as possible.

The second is when you are tackling these domains that are not very well explored, you can get ambitious. Many people go into this space saying there’s so many ways they can make an impact, and wonder, ‘how do I generate a dataset that’s able to answer 50,000 questions at once?’ But you will face shareholder pressure at some point to bring something to market. You want to be close to the point where you can actually flip the switch and say, ‘we’re going to pick a horse and go,.’ You don’t want to build up a lot of know-how, or infrastructure, or technology and you’re still not sure of the greatest market-entry or product fit for what you’re developing. Keep that in the back of your mind: balance your ambition of where you think the company could go with the real-world demand.

What does Women’s History Month mean to you, and why is it so important that we celebrate it?

It’s nice to have an opportunity to pause and take notice of the contributions that women have had in so many facets of our life. But also, to acknowledge the things that plague them.

We develop diagnostics for women’s health issues. What I appreciate about having the entire month set aside is it is a forced opportunity, where despite any interest or even lack of interest you may have, your [social media] feed is going to be filled with people talking about women’s health issues. We’re going to join in the foray and make sure that, to the extent that you’re paying attention, you have an opportunity to learn something new about female-born bodies. And that’s great.