March 22, 2023

Member Spotlight: Gilead Sciences

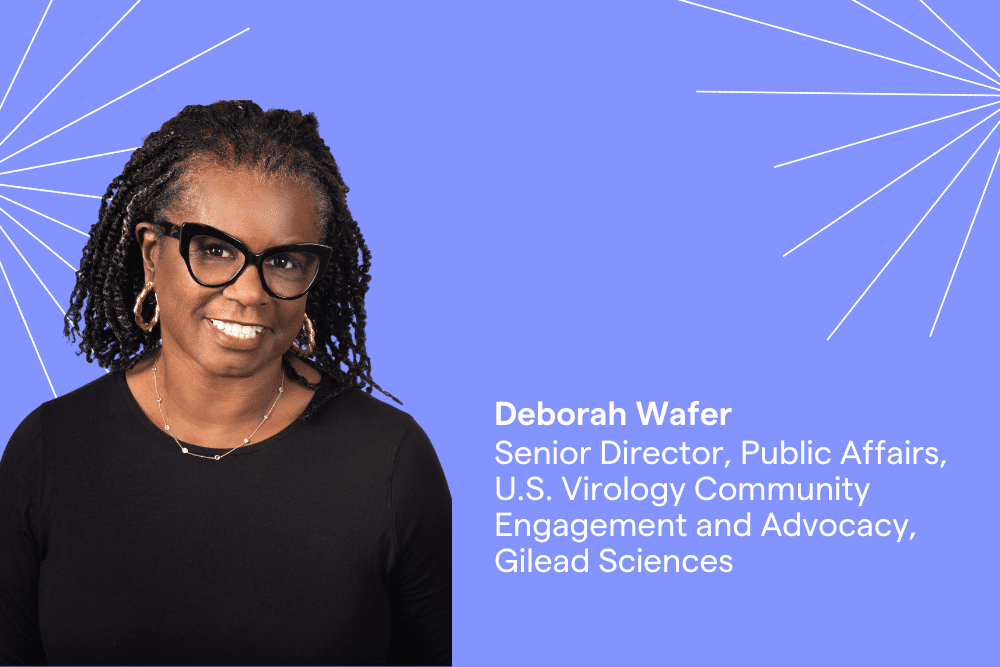

Deborah Wafer’s Decades-Long Commitment to Women’s Health and Serving Marginalized Communities Made an Impact in the HIV Epidemic

Deborah Wafer has been devoted to advocating for women’s and public health issues for more than three decades and is an expert in HIV education and prevention. As senior director of public affairs of U.S. virology community engagement and advocacy at Gilead Sciences, she focuses on partnerships with advocates and community-based organizations to help end the HIV epidemic. Gilead Sciences has been a leader in developing antiretroviral treatments for HIV, and has nearly one dozen commercially available medications in its portfolio including its newest treatment, Sunlenca.

As a longtime nurse practitioner and physicians’ assistant in her native Los Angeles, Deborah saw first-hand the effects of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1990s, especially the impact on the Black community and pregnant women and their infants. While working as a clinician at UCLA Medical Center in the Clinical AIDS Education and Research Center (CARE Center), she coordinated clinical trials for people living with HIV and played a critical role in determining research protocols for a study on decreasing perinatal transmission of HIV. During the ‘90s, nearly a third of pregnant women who were HIV-positive transmitted the virus from mother to baby, but thanks to the research Deborah worked on the number of perinatal HIV transmissions is down by 95 percent today.

Deborah was a featured speaker at our Black Biotech Trailblazers panel in the Bay Area earlier this year. In honor of Women’s History Month, we are sharing Deborah’s story and celebrating her career and achievements, talk about her continuing work in HIV education and prevention, and ask what advice she has for the next generation of life scientists.

How did you get started in healthcare?

I started getting interested in healthcare when the Black Panthers had free clinics, and they were screening for sickle cell disease. I have two brothers who were born with sickle cell—we didn’t know what it was, how it affected the family, or any of that. In college, I majored in health education but I also volunteered at the Black Panthers’ Free Clinics to do education around sickle cell. I was fortunate very early on in my career as a health educator and as a student, and having grown up in South Central Los Angeles, that I worked with Dr. David Satcher. He had come to King/Drew Medical Center to set up the Sickle Cell Center. Dr. Satcher went on to become head of the CDC and the Surgeon General for the Clinton administration—I had no idea who he was then! [laughs]

He motivated me and my colleagues around how we could be change agents in our community with knowledge and outreach. Since we were the ones who got the education, we had a duty to stay in the community and make sure that this knowledge was spread. I started as a health educator and went into the PA program, which gave me the opportunity to examine and talk to patients, and see a lot of different healthcare issues.

When did you make the transition to biotech?

I was doing community outreach at UCLA on pregnancy and women’s health. I knew the OB-GYN doctors in the community, and sometimes people from pharma companies would call on me. One day, the person who was a community liaison for a biotech company said he was getting another job. I asked him: ‘What do you do every day?’ Once he told me, I was interested. He never thought that I would leave patient care, but once I interviewed for the job, I realized it was a much bigger reach—with a much bigger budget—to do the kind of education that I thought was important.

I became a community liaison with that company, which was later acquired by Pfizer. I moved to New York and did direct-to-patient marketing and community marketing for their HIV product. I came to Gilead at a pivotal point for the company, when they developed the first once-a-day treatment for HIV [Atripla], and I did community marketing. Previously, I wasn’t able to have this kind of impact—with Gilead’s support, I could go to 12 different cities and do innovative programming that would have the community engaged. What I saw was a bigger opportunity to do community outreach and education.

You played an important role in coordinating clinical trials that led to the development of treatments that drastically reduced the perinatal transmission of HIV. What was one of the biggest challenges of working in the HIV field in the 1990s?

When you talk about perinatal transmission back in the late nineties, there were studies that were done—and it was revolutionary because it was a study where you had to be pregnant and HIV-positive (in most clinical studies, the last thing you want is a pregnant woman.) We knew that about 25 to 32 percent of women transmitted the virus from mother to baby. In a double-blind study, some mothers were treated with antiretrovirals and others were not. In women that were treated, they found the viral loads were decreased to a level that they did not transmit the virus.

The thought was: if we can lower the viral load, there’s no virus to transmit to the baby. We needed to find out if transmission happened in utero or during the birth process, which blood samples could determine. Mothers were treated with medication during the pregnancy and at delivery, and infants were treated for the first six weeks of their life. Transmission rates went down, as it’s been biologically tested and proven that if your viral load is undetectable, then there’s no way you can transmit the virus.

One of the challenges that we had to work on with HIV was stigma. Back then, when recommending medication to pregnant women, providers used to say: ‘You don’t want to give your baby AIDS, do you?’ Of course nobody wants to ‘give’ their baby AIDS. We’re talking about the transmission of a virus, and then we’re talking about someone acquiring the virus. That was something that we worked on a lot with healthcare providers: language is important, and don’t phrase it that way. Tell the patient that if they don’t take this medicine, the viral load may not be low enough to prevent transmission of the virus.

Things have come so far for women’s health and HIV treatment since. What do we still have to work on?

We still have a lot of work to do, especially with Black women. Black women have the highest rate of HIV acquisition in the country, more than any other group followed by Latino women. It’s because of long-standing health inequity, political and social determinants of health, and lack of screening. We now have more prevention methods, so we can do a better job. But all of that has to do with stigma, equity, and access.

And then there’s the issue of knowledge—provider knowledge and patient knowledge—about HIV. There is also a lack of conversations from providers about sexual health. You won’t know what’s wrong with people unless you talk to them, and sex still seems to be a hard thing for clinicians to talk about with patients, and vice versa.

Lastly, every pregnant woman should have an HIV test. This is not about risk-based—you need to know your HIV status because if you have it, there’s treatment to prevent transmission. Sometimes, if a woman has not had any prenatal care and comes in [to the hospital] and delivers, you might miss an HIV transmission.

I never would’ve thought I would have the job that I have now. When I was growing up, I didn’t know anybody who worked for pharma, and I didn’t know anybody who was a professional in the medical world. Being around other women—and having other women pull me in and teach me and take me places and show me things—opened up a whole new world for me. Celebrating women helps everyone to see what is possible.

What is the biggest challenge you’ve had to overcome in your career?

I think the biggest challenge is dealing with health equity. Black people are at the top of many lists of being the most impacted by certain diseases, breast cancer being one of them. Black women don’t have more breast cancer than white women, but the mortality rate is higher in Black women than it is in white women. It’s not that more Black women have it, it’s that they are seen later in the disease state.

What’s your biggest work-related challenge today?

In my new job, I have an even bigger platform so I’m not working in one disease state. And there is still the challenge of addressing stigma in the HIV population—because stigma, miseducation, and disinformation are some of the things that keep people out of receiving healthcare.

A recent article in Bloomberg says a large percentage of Generation X women executives—women in their 40s and 50s—are leaving the workforce “in droves.” The article cites a lack of support for mothers both at work and at home. What can life science companies learn from this, and how can they attract and retain more women in leadership roles?

For many women, when you’re young and moving up in your job is also when you’re having children. Corporate America demands a lot of you, especially if you’re traveling. When you have a three-year-old or a five-year-old, you don’t want to leave them during the day with just anybody, even though you may trust them. That’s also the time where there are so many pivotal moments in your kids’ life. When you get to your fifties, you may not have to think about those things, but do people still value you? You also don’t have the energy that you had back when you were young. It is a very interesting cycle.

I believe job sharing (which was done in the ‘90s) can help, and having more childcare on site and offering support services (such as well-being services) could be a solution so that women don’t have to make those decisions about their family and their home.

What does Women’s History Month mean to you, and why is it important that we celebrate it?

It’s important that we celebrate it because we run the world! [laughs] This month reminds us of who we are, and I do think that women need to celebrate each other more, and we need to celebrate for younger women. I have a daughter who’s a journalist and I’m very proud of what she’s doing. I know that part of what shaped her career is from traveling with me, seeing other women do things and knowing what is possible.

I never would’ve thought I would have the job that I have now. When I was growing up, I didn’t know anybody who worked for pharma, and I didn’t know anybody who was a professional in the medical world. Being around other women—and having other women pull me in and teach me and take me places and show me things—opened up a whole new world for me. Celebrating women helps everyone to see what is possible.

What advice do you have for up-and-coming life scientists, especially young women?

Two things: One is be curious. Never stop being curious. And the second is to be fearless. If you make a mistake, learn from it and move on but don’t punish yourself.

I think curiosity is important, and that a lot of women have good questions, but sometimes because of the dynamics that get played out they don’t ask them. That’s when you don’t want to be fearful and you should move with your heart. I think your heart always leads you to the right place.